The Jargon Bubble

You are a CEO. You negotiate million-dollar deals. But when your US lawyer sends you the "Terms of Service" update, you pass it to your assistant. "I can't read this. It's gibberish."

It's not gibberish. It's Legalese. And unlike Medical English (which is hard because it's precise), Legal English is often hard because it's designed to be exclusionary.

It is a "Jargon Bubble." Inside the bubble, lawyers speak to lawyers. Outside the bubble, you (the client) are left in the dark.

In this deep dive, we will puncture the bubble, explaining the Modal Verbs of Obligation, the Rule of Three, and why contracts are written in 18th-century code.

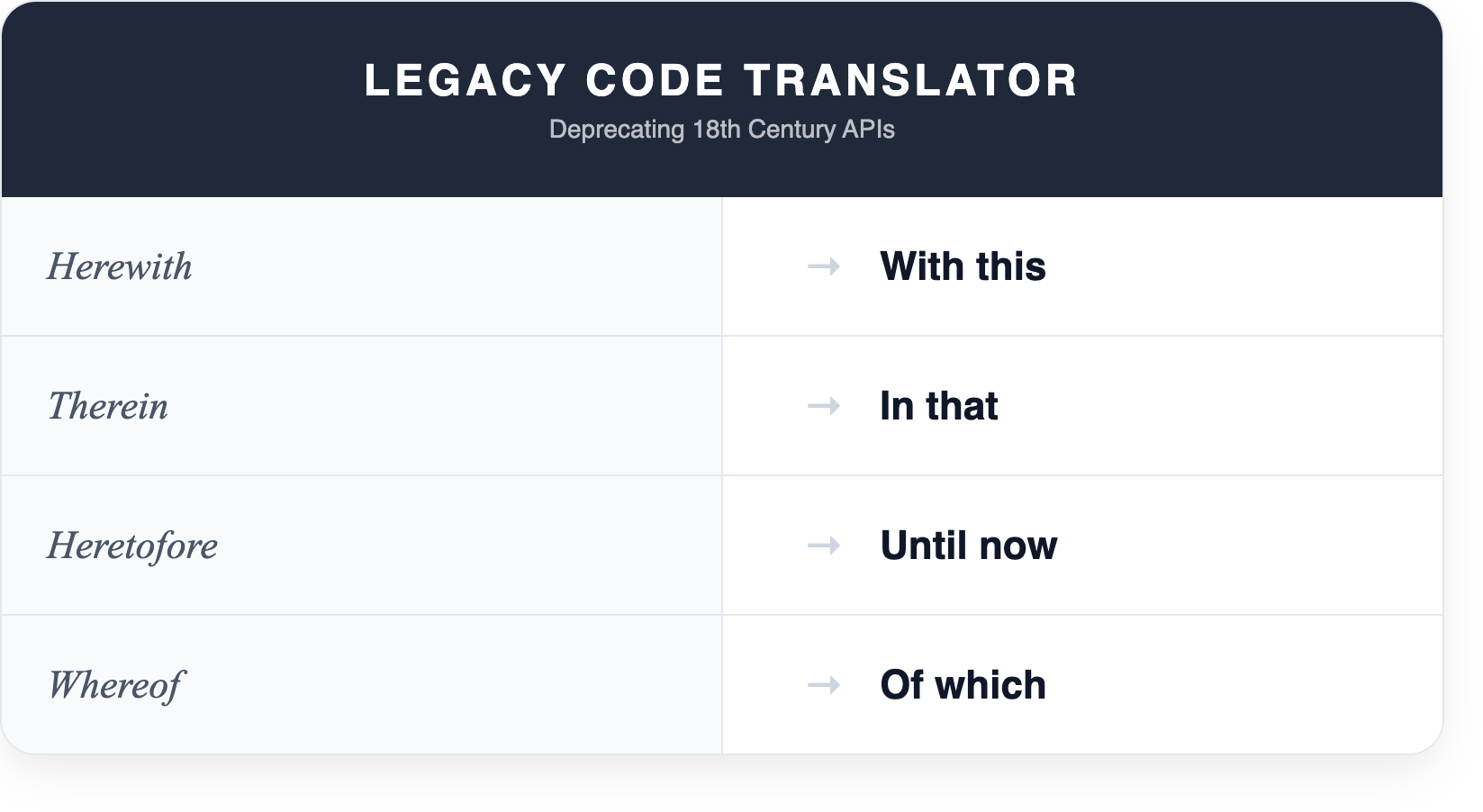

Part 1: The "Herewith" and "Therein" (Archaic Adverbs)

Legal English is stuck in the 18th Century. It loves Archaic Pronominal Adverbs.

- Herewith: With this letter.

- Therein: In that document.

- Heretofore: Up until now.

- Whereof: Of which.

These words serve zero communicative purpose in 2024. They are purely Signaling. They signal: "This is a serious legal document written by a serious lawyer." They add cognitive load without adding meaning.

Text Clarifier Hack: Our tool ruthlessly deletes these. "The parties associated herewith..." -> "The people involved..." The legal binding power is the same. The readability goes from F to A.

Part 2: The Doublet Phenomenon (Null and Void)

Why do lawyers say "Null and Void"? Why "Cease and Desist"? Why "Give and Bequeath"?

This is a historical hangover from the Norman Conquest of England (1066). The courts had to speak both English (Germanic) and French (Romance) to be understood by peasants and nobles. So they used pairs to cover both bases:

- Cease (French) + Desist (French/Latin).

- Will (English) + Testament (French).

- Goods (English) + Chattels (French).

Today, we don't need both. "Null" means "Void." But the tradition (Fossilization!) remains. You are reading double the words for half the meaning.

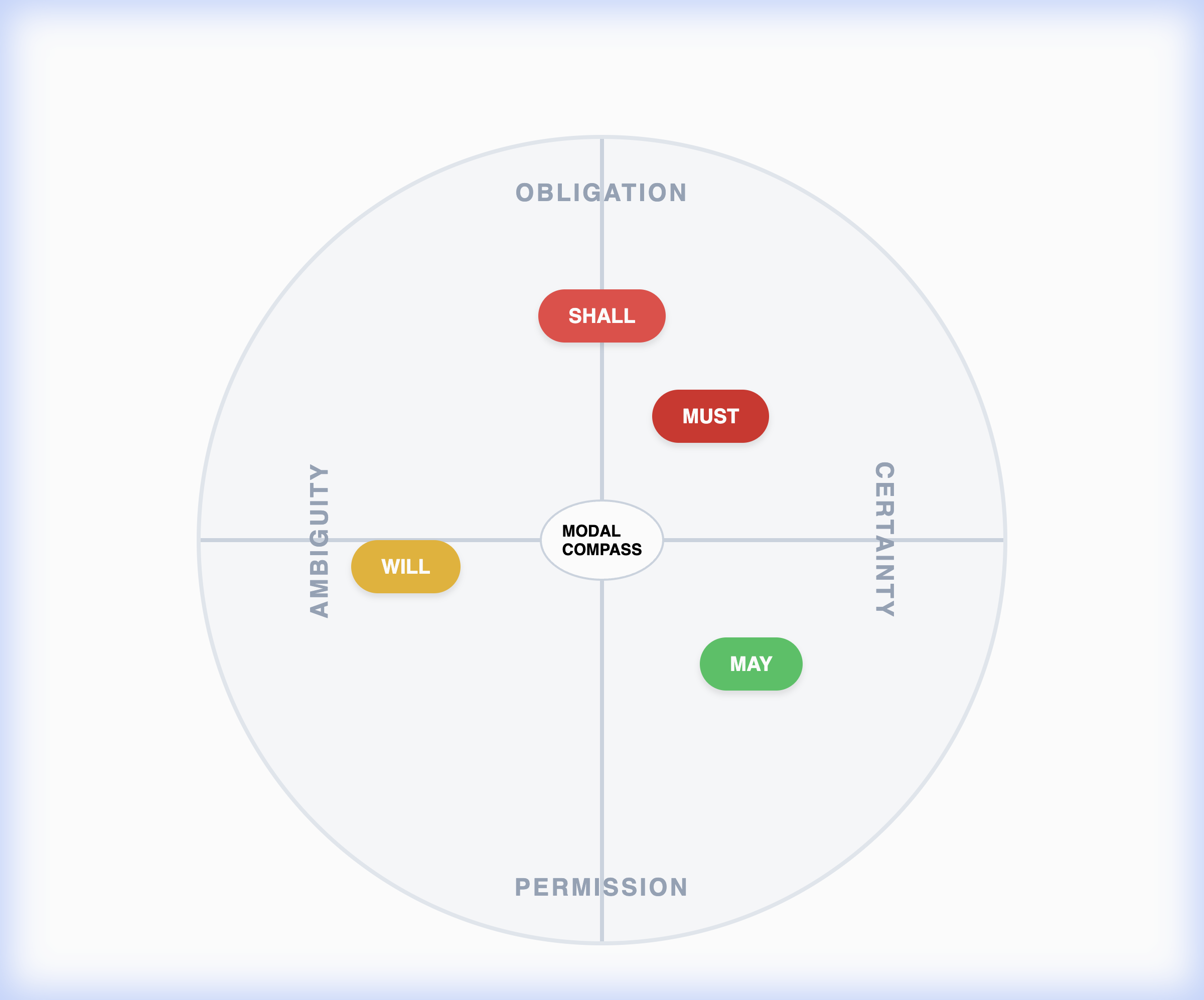

Part 3: The "Shall" vs "Will" Confusion (Modal Verbs)

In normal English, "Shall" is dead. In Legal English, "Shall" is God. It is the Modal Verb of Obligation.

- "The Tenant shall pay rent." = Must pay.

- "The Tenant may pay rent." = Optional.

- "The Tenant will pay rent." = Prediction (Future).

Sloppy drafting often mixes "Shall," "Will," "Must," and "Undertakes to." For a non-native speaker, this modal verb ambiguity is a nightmare. Does "The company will provide" mean a promise or a prediction? In court, that difference costs millions.

The Rule: If you see "Shall," replace it mentally with "Must." If you see "May," replace it with "Can."

Part 4: Case Study: De-coding a Terms of Service

Let's look at a standard clause:

"Notwithstanding anything to the contrary herein, the Provider shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or indirect damages."

Step 1: The "Notwithstanding" Trap "Notwithstanding anything to the contrary herein" is a "Trump Card." It means: "Ignore everything else in the contract; THIS sentence wins." It is a logical operator.

Step 2: The List of Damages "Incidental, Consequential, Indirect." This is the "Kitchen Sink" approach. They are listing every synonym for "Bad Stuff" to prevent you from suing.

Step 3: The Clarification "Even if we said the opposite earlier, we are not responsible if you lose money because our service broke."

Text Clarifier strips the "Notwithstanding" and "Consequential" padding, revealing the core logic: No Liability.

Part 5: The "Reasonable Person" Standard

A huge part of Legal English is vague on purpose.

- "Within a reasonable time."

- "Use best efforts."

- "Material breach."

What is "Reasonable"? 2 days? 2 months? This ambiguity allows judges to decide later. For a learner, this is terrifying. You want a dictionary definition. But in Law, there is no definition. There is only Precedent. "Reasonable" means "What a normal person would do."

Part 6: Conclusion

Don't let the Jargon Bubble intimidate you. Legalese is just Bad Writing with a Tie. It violates every rule of modern clear communication.

Use tools to puncture the bubble. Translate the "Herewiths" to "Heres." Translate the "Null and Voids" to "Inválidos." Once you strip away the 18th-century costume, the logic is usually simple: "If you break this, you pay me."

References:

- Garner, B. A. (2013). Legal Writing in Plain English.

- Tiersma, P. M. (1999). Legal Language.

- Mellinkoff, D. (1963). The Language of the Law.