Depth of Processing: Why Harder Definitions Create Stronger Memories

We have all been there.

You are reading a book in Spanish or French. You see a word you don't know: "Épouvantable". You open Google Translate. It says: "Terrible". You nod, say "Ah, okay," and go back to reading.

Three sentences later, you see "Épouvantable" again. And you stare at it blankly. You have zero memory of what it means. You have to look it up again. And again. And again.

Why does this happen? You aren't stupid. You have a functioning hippocampus. Why did the information evaporate instantly?

The answer lies in a fundamental principle of memory science called the Levels of Processing Framework, first proposed by Craik and Lockhart in 1972, and later applied to language learning by researchers like Thompson (1987).

The science tells us a hard truth: You forgot the word because looking it up was too easy.

In this deep dive, we will explore the neuroscience of memory formation, why "Efficiency" is the enemy of "Retention," the biological mechanism of Long-Term Potentiation, and why switching to a Monolingual Dictionary (finding explanations in the target language) is the single most powerful change you can make to your vocabulary workflow.

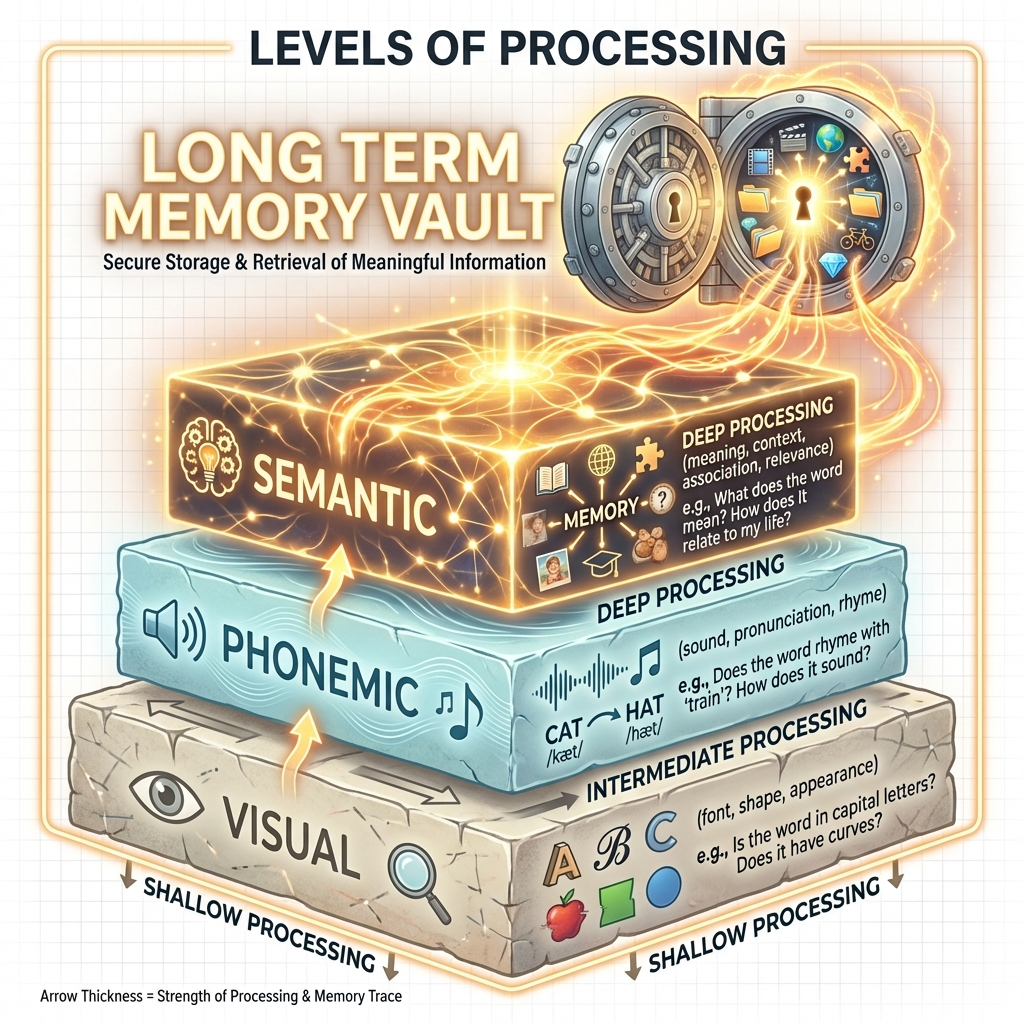

Part 1: The Shallow vs. The Deep (Craik & Lockhart 1972)

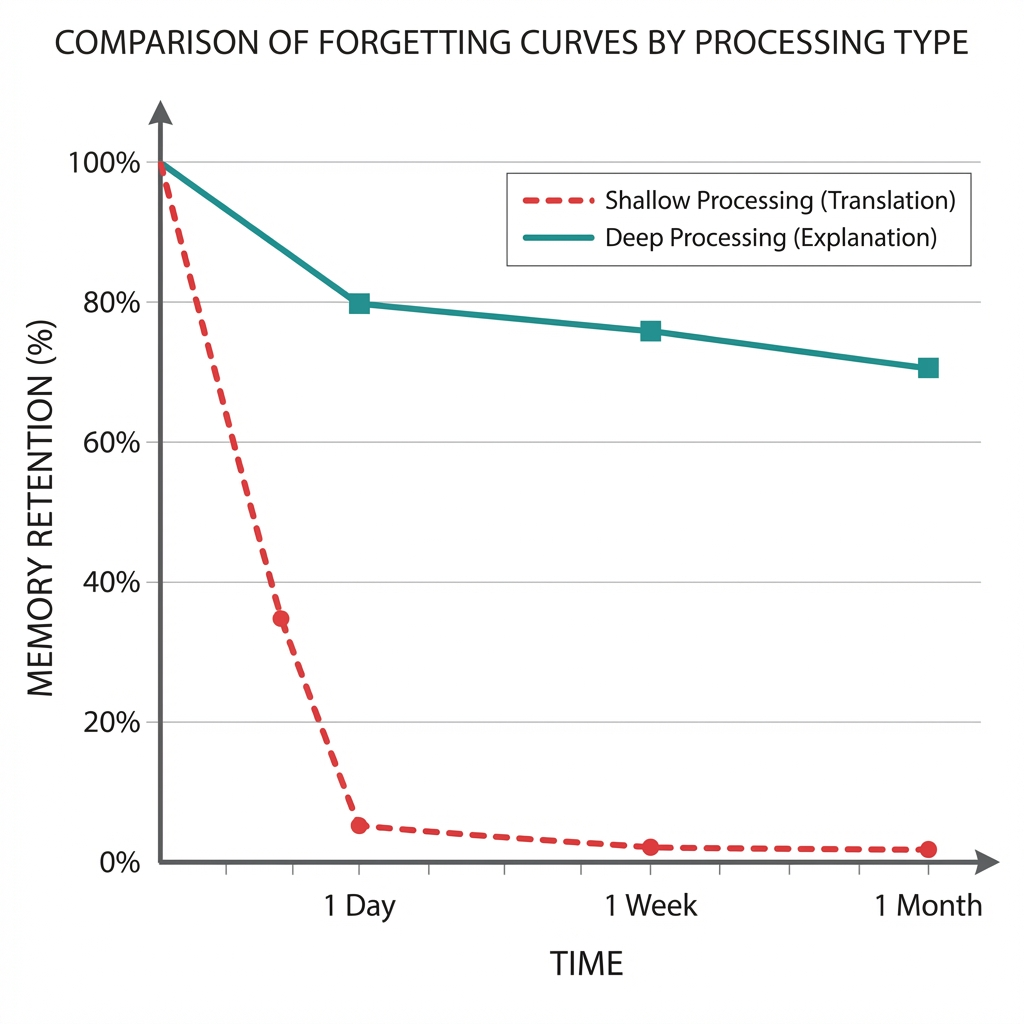

Before 1972, psychologists thought memory was just about Rehearsal. If you repeated a word enough times (rote memorization), it would stick. Craik and Lockhart blew this theory up. They argued that repetition is weak. What matters is Depth.

They proposed that memory is a byproduct of processing. The more deeply you process a piece of information, the stronger the memory trace.

Level 1: Structural Processing (The Shallowest)

This is processing the physical appearance of the word.

- Task: "Is the word written in Capital Letters?"

- Result: Almost zero memory retention. You saw the ink, not the word.

Level 2: Phonemic Processing (Mid-Shallow)

This is processing the sound.

- Task: "Does 'Cat' rhyme with 'Hat'?"

- Result: Weak memory retention. You heard the sound, but not the idea.

Level 3: Semantic Processing (The Deepest)

This is processing the meaning and relationship to other ideas.

- Task: "Is a Cat a mammal? Does it have fur? Do I like Cats?"

- Result: Strong memory retention.

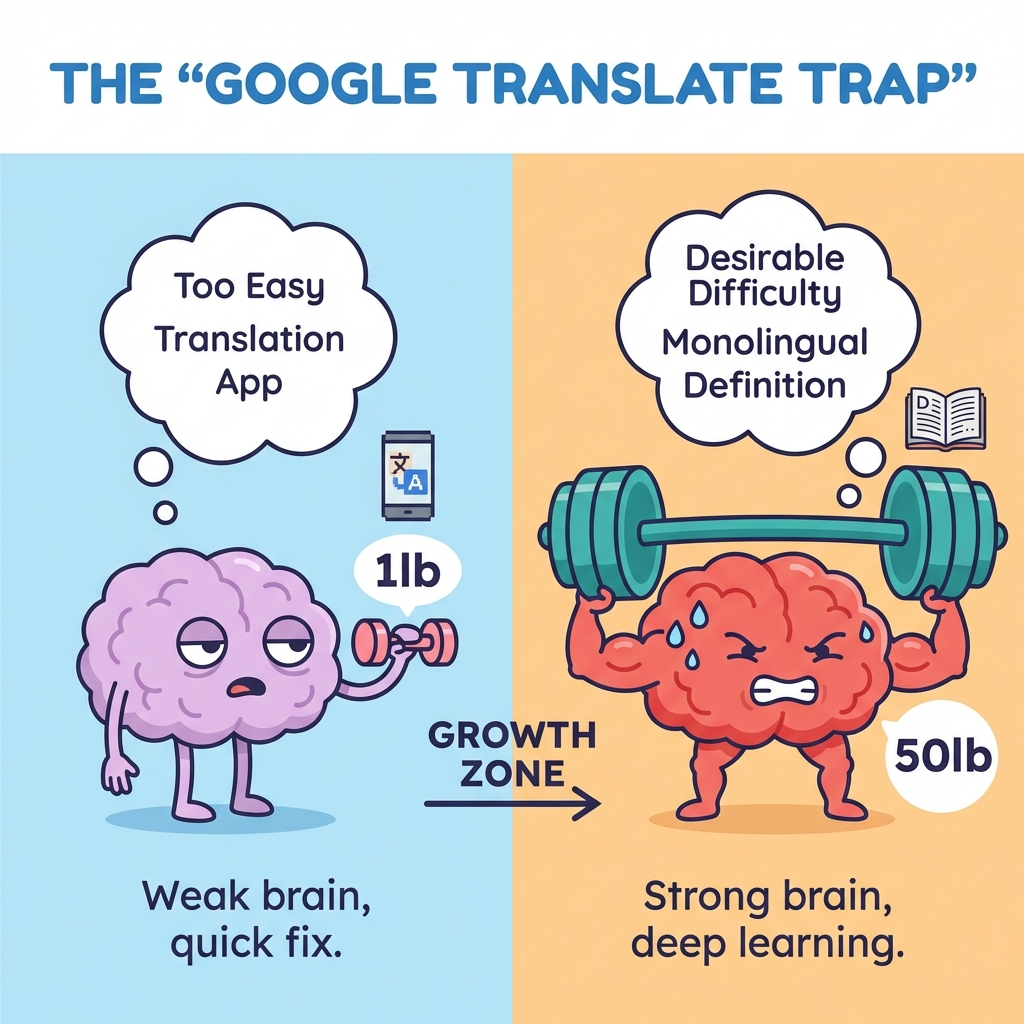

The "Google Translate" Trap

When you use a bilingual translator ("Épouvantable = Terrible"), you are engaging in extremely shallow processing. You are essentially doing a "Search and Replace" operation.

- You don't process the nuance.

- You don't visualize the concept.

- You don't connect it to other French words.

You simply map Symbol A to Symbol B. It is a "Low-Cognitive Load" event. And because the brain is efficient, it discards Low-Load events as "Noise."

Part 2: The Neuroscience of Encoding (Why "Hard" Works)

To understand why depth matters, we have to look at the biology of the synapse. Memory is not a file stored on a hard drive; it is a physical connection between neurons. This connection is strengthened by a process called Long-Term Potentiation (LTP).

The Hippocampus as the Gatekeeper

The Hippocampus is the part of your brain that decides what becomes a long-term memory. It acts like a Bouncer at a club.

- Routine Information (The Translate App): "This is easy. I've seen 'Terrible' a million times. Let it pass through. Don't waste energy storing it."

- Novel/Challenging Information (The Monolingual Definition): "Whoa. What is this? I have to read this sentence three times to understand it. I have to visualize a 'scary situation.' This seems important. Encode it!"

Desirable Difficulty (Bjork 1994)

In 1994, Robert Bjork coined the term "Desirable Difficulty." He argued that learning tasks that are frustratingly hard lead to better long-term retention than tasks that are easy.

Think of it like lifting weights.

- Google Translate is lifting a 1-pound pink dumbbell. It is easy. You can do 100 reps (look up 100 words). But you will build zero muscle.

- Monolingual Definition remains the 50-pound dumbbell. It is hard. You struggle. You sweat. But that struggle is the signal to your body to build muscle.

Part 3: The Thompson Study (1987)

G. Thompson tested this explicitly in his seminal study "Using Bilingual Dictionaries." He compared groups of learners:

- Group A: Used Bilingual Dictionaries (L2 -> L1).

- Group B: Used Monolingual Dictionaries (L2 -> L2 Explanation).

The Results: Group B described the task as "annoying" and "slow." However, on vocabulary retention tests held weeks later, Group B obliterated Group A.

Why? Let's trace the cognitive steps:

Scenario: Defining "Resilient"

The Bilingual User:

- Input: "Resilient"

- Output: "Tough"

- Time: 0.5 seconds.

- Neurons Fired: ~1,000.

The Monolingual User:

- Input: "Resilient"

- Definition: "Able to withstand or recover quickly from difficult conditions."

- Cognitive Step A: "Withstand." (Visualize a shield? A wall?).

- Cognitive Step B: "Recover quickly." (Visualize a spring? A rubber band?).

- Cognitive Step C: "Difficult conditions." (Visualize a storm? A war?).

- Synthesis: "Ah! It's like a person who gets knocked down but gets back up."

- Time: 12 seconds.

- Neurons Fired: ~1,000,000.

This process required you to access 5-6 widely distributed concepts in your brain. You created a "Semantic Web" around the new word. That web is sturdy. It sticks. The Bilingual trace is basically a single string. If that string snaps, the word is gone.

Part 4: The Generation Effect (Slamecka & Graf 1978)

Here is another SEO-gold cognitive principle: The Generation Effect.

This principle states that information you generate yourself is better remembered than information you simply read.

- Read: "hot-cold" (Weak memory).

- Generate: "hot-c___" (Strong memory).

When you use a Monolingual Dictionary, you are often forced to Generate the meaning. The definition gives you the clues, but you have to solve the puzzle.

- Clue: "A vehicle for transporting many people."

- Your Brain: "Is it a bus? Yes, it's a bus."

That micro-second where you "solved" the definition is a Generation Event. You created the meaning. You own it. When you use Google Translate, you are just reading. You are a passive consumer of data.

Part 5: The "Tip of the Tongue" Phenomenon

Another benefit of Deep Processing is avoiding the "Tip of the Tongue" syndrome. This happens when you know a word, but you can't access it. This usually occurs because the "retrieval path" is too narrow.

If you learned "Mesa = Table," you have exactly one retrieval path. If that one wire is cut (you forget the association), the word is gone.

If you learned "Mesa = A piece of furniture with four legs where we eat dinner," you have multiple retrieval paths.

- If you think of "Furniture," you might trigger "Mesa."

- If you think of "Dinner," you might trigger "Mesa."

- If you think of "Four legs," you might trigger "Mesa."

Monolingual definitions create redundant neural pathways. They act as a safety net. Even if you forget the exact translation, you remember the description, which allows you to circumlocute (describe your way around the missing word)—a key trait of fluent speakers.

Part 6: The Fear of Logic (Why We Avoid It)

If the science is so clear, why does everyone still use Google Translate? Why is Duolingo (which is pure translation) a billion-dollar company?

1. The Path of Least Resistance Our brains are energy-conserving machines. We are biologically wired to avoid cognitive effort. When given the choice between "Easy Answer" and "Hard Answer," the primitive brain screams "Easy!" You have to consciously override this instinct.

2. The "Ambiguity Intolerance" Beginners are terrified of not understanding 100%. A monolingual definition often leaves some ambiguity.

- Definition: "A large vehicle used for transport."

- Learner: "Is it a bus? A truck? A van? I don't know exactly!"

They panic. They check the translation to be "sure." But surprisingly, Ambiguity is good for memory. The lingering question mark keeps the brain active. The brain keeps working on the puzzle in the background (the Zeigarnik Effect).

3. The Speed Illusion Translation feels faster. You get through the page faster. But "reading speed" is a vanity metric if your "retention rate" is zero. You are efficiently wasting your time.

Part 7: The "Text Clarifier" Solution (Adaptive Depth)

Historically, Monolingual Dictionaries (like the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary) had a problem: They were circular. You look up a hard word, and the definition contains more hard words. You go down a rabbit hole of confusion.

This is where Text Clarifier fundamentally upgrades the Thompson model. Our AI uses Adaptive Simplification.

When you highlight a difficult word, we don't just give you a generic dictionary definition. We generate a Context-Specific Explanation using simple vocabulary (usually the top 2000 most common words).

- Hard Word: "The politician obfuscated the truth."

- Dictionary: "To render obscure, unclear, or unintelligible." (Too hard!)

- Text Clarifier: "He made the truth confusing on purpose to hide it." (Simple!)

We provide the Depth of Processing (you have to read the explanation) without the Frustration (the explanation is easy to understand).

This strikes the perfect balance:

- Enough Effort to trigger memory formation (Desirable Difficulty).

- Enough Clarity to ensure comprehension (i+1).

Part 8: Practical Protocols for Deep Processing

How can you implement this in your daily study routine?

Protocol 1: The "Guess First" Rule

Before you click on a word, force yourself to spend 3 seconds guessing the meaning from context.

- Context: "The dog wagged his tail."

- Guess: "It's the thing at the back of the dog." Even if you are wrong, the act of predicting primes the brain to receive the answer.

Protocol 2: The Visual Anchor

Don't just write down the definition. Draw a terrible stick-figure picture next to it.

- "Run" -> Draw stick legs.

- "Eat" -> Draw a mouth. Since the brain processes visual data 60,000x faster than text, this creates a massive "Dual Coding" memory hook.

Protocol 3: The "Explain to a 5-Year-Old" technique (Feynman Technique)

When you learn a new word, pretend you have to explain it to a child in the target language.

- Word: "Democracy."

- Explanation: "It is when everyone chooses the leader." If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it deeply.

Part 9: Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can I use Bilingual Dictionaries at all? A: Yes, in the first 2-3 months (A0/A1 level). When you know zero words, you have no foundation to build explanations on. You need the "Seed Vocabulary." But as soon as you hit A2 (Conversational), switch to Monolingual immediately.

Q: It takes me 2 minutes to read one page now. Is that okay? A: Yes. Stop measuring "Pages per Hour." Start measuring "Synapses per Hour." One page read deeply is worth 50 pages skimmed.

Q: What if the Text Clarifier explanation is also too hard? A: This means your "Input" material is too advanced (i+10). Drop down a level. Read a children's book or a news article written for students. If you are looking up every 3rd word, you aren't reading; you are deciphering.

Q: Does this work for flashcards (Anki)? A: Yes! Most people make "Front: Spanish / Back: English" cards. Change your cards to: "Front: Spanish / Back: Easy Spanish Definition + Image." It will make your reviews slower, but your retention rate will skyrocket.

Part 10: Conclusion

If you want to remember more, you have to work harder. It sounds counter-intuitive in our age of "Convenience," but convenience is the enemy of memory.

- Translation is Fast Food. It satisfies you instantly, but leaves you nutritionally empty.

- Explanation is a Home-Cooked Meal. It takes longer to prepare, requires effort, but it sustains you.

Next time you see a word you don't know, fight the urge to translate. Ask "What does this mean?" not "What is this in English?" Sit with the definition. Wrestle with the concept. The struggle is not a sign that you are failing. It is the sound of your brain growing.

Part 11: The History of the Dictionary (Samuel Johnson vs Modern Learners)

To appreciate why Monolingual dictionaries are revolutionary, we must understand their history. In 1755, Samuel Johnson published his "Dictionary of the English Language." His goal wasn't just to list words. It was to define the "Soul" of the concepts.

Johnson's Approach: He didn't just say "Oats = Grain." He famously defined Oats as: "A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people."

This definition is rich. It has cultural context (England vs Scotland). It has humor. It has depth. When you read it, you remember it.

The Modern Bilingual Degradation: Modern digital dictionaries have stripped the soul out of definitions in the name of efficiency. Dictionary.com defines Oats as: "A cereal plant cultivated chiefly in cool climates." Google Translate defines Oats as: "Avena" (Spanish).

We have optimized for speed at the cost of "Stickiness." The Monolingual learner is effectively returning to the Samuel Johnson era. By reading a full explanation, you get the context, the nuance, and the story. You aren't just downloading data; you are engaging with literature.

Part 12: Cognitive Load Theory in Depth (Sweller 1988)

John Sweller's Cognitive Load Theory adds another layer to our understanding. He distinguishes between three types of load:

- Intrinsic Load: How hard the clear task is (e.g., Understanding the word definition).

- Extraneous Load: Useless effort caused by bad design (e.g., A messy interface or confusing grammar).

- Germane Load: The "Good" effort used to build schemas (memories).

The Magic of Text Clarifier: Text Clarifier reduces Extraneous Load by stripping away complex grammar from the definition. But it increases Germane Load by forcing you to process the meaning in L2.

If you use a Bilingual dictionary, you effectively remove the Germane Load. You make the task "Too Easy." If you use a native dictionary (like Oxford), the Intrinsic Load might be too high (the definition is too hard).

We aim for the "Goldilocks Zone" of Cognitive Load:

- Intrinsic: Low (Simple definition).

- Extraneous: Low (Clean UI).

- Germane: High (You must process meaning in L2).

Part 13: The Role of Sleep in Processing (Consolidation)

Why do "deeply processed" memories stick? Because of what happens when you sleep. During Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS), the Hippocampus "replays" the day's events to the Neocortex. This is called Memory Consolidation.

Tagging for Replay: The brain cannot replay everything. It has to prioritize. It prioritizes memories that were "Emotionally Salient" or "Cognitively Taxing."

- Scenario A: You looked up "Dog = Perro". Low tax. Brain tags as "Low Priority." Result: Deleted during sleep.

- Scenario B: You struggled for 10 seconds to understand a description of a dog. High tax. Brain tags as "High Priority." Result: Replayed and Consolidated.

If you don't struggle, you don't get the "Sleep Tag." This is why you can study on Duolingo for 30 minutes, go to sleep, and wake up remembering nothing. You didn't give your brain a reason to save the file.

Part 14: Case Studies (Medical School Parallels)

We can see the "Depth of Processing" effect clearly in Medical School students. Med students have to memorize thousands of anatomical terms.

Study: Rote vs Concept Mapping

- Group A (Flashcards): Memorized "Mitral Valve = Valve between Left Atrium and Ventricle."

- Group B (Concept Mapping): Had to draw the heart and explain why the valve is needed there (to prevent backflow during systole).

Result: Group A passed the multiple-choice test the next day but failed the clinical reasoning test 6 months later. Group B retained the knowledge for years.

Application to Language: You are a language medical student. Don't be Group A. Don't memorize "Mesa = Table." Be Group B. Understand "Mesa" as a functional component of a dining room. Draw the map. Explanation is concept mapping.

Part 15: Advanced "Monolingual" Drills

For the advanced learner (B2+), here are "High Intensity" drills to maximize Depth of Processing.

1. The "Reverse Definition" Drill

- Take a common word (e.g., "Car").

- Write your own monolingual definition for it.

- "A machine with four wheels that uses gasoline to move people."

- This forces you to generate language to describe a simple concept. It is cognitively exhausting but incredibly effective.

2. The "Taboo" Game

- Play with a partner or AI.

- You have to describe a word without using the 3 most common associated words.

- Describe "Coffee" without using "Drink," "Morning," or "Caffeine."

- "A black liquid made from beans that gives you energy."

3. The "Synonym Ladder"

- Start with a simple word: "Good."

- Find a slightly harder synonym: "Great."

- Find a harder one: "Excellent."

- Find a specific one: "Superb."

- Find a very specific one: "Exquisite."

- For each step, explain the difference in meaning in L2. (e.g., "Exquisite is more delicate than Superb").

By engaging in these drills, you are constantly "Deepening" the channel. You are turning a shallow stream of vocabulary into a deep river of fluency.

References & Further Reading:

- Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior.

- Thompson, G. (1987). Using bilingual dictionaries. ELT Journal.

- Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings.

- Slamecka, N. J., & Graf, P. (1978). The generation effect: Delineation of a phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Psychology.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science.