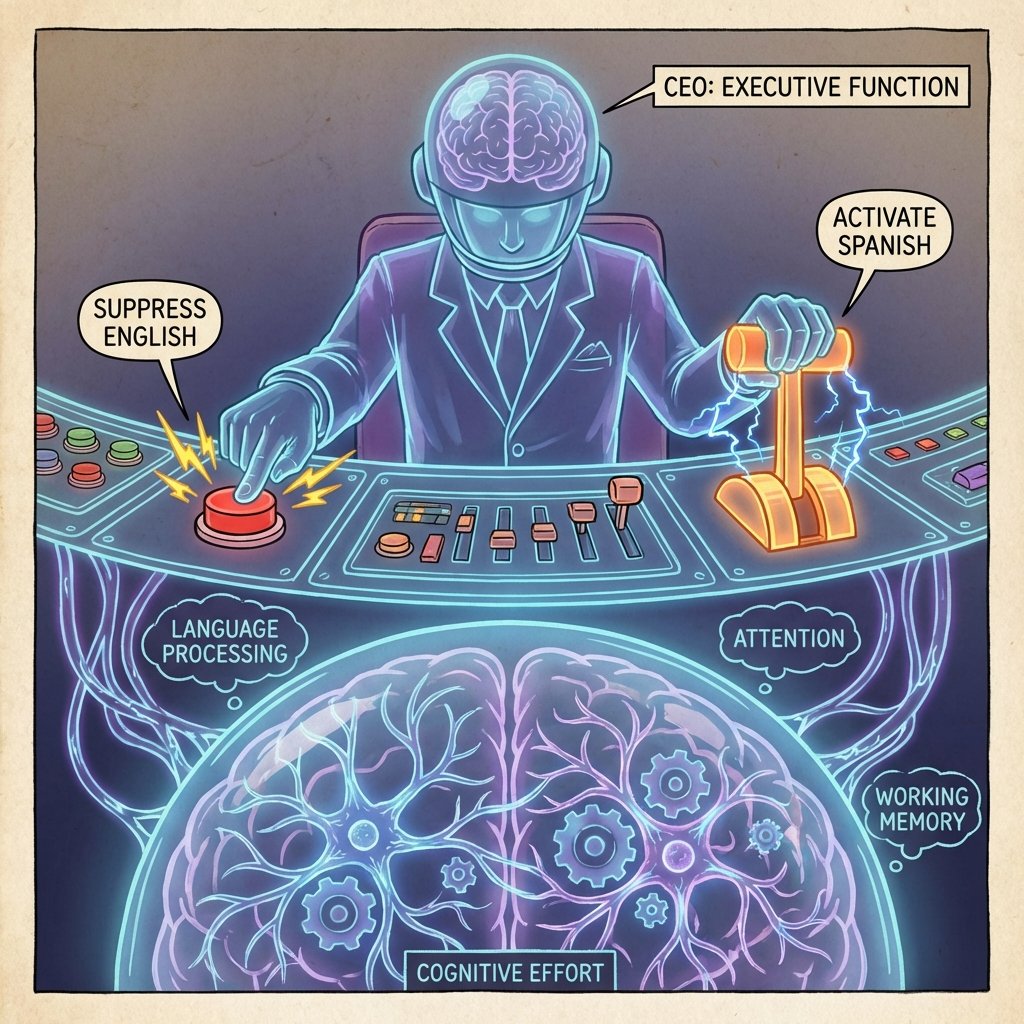

The Bilingual Brain is a CEO: How Inhibitory Control Works

There is a myth that bilingual people are "smarter" than monolinguals. Parents rush to put their toddlers in immersion schools, hoping it will raise their IQ to genius levels. The internet is flooded with articles claiming that learning Spanish will make you a math genius or a chess grandmaster.

But does learning French actually make you better at Math? Does learning Spanish make you a better driver? Can speaking Japanese help you solve complex logic puzzles faster? Strictly speaking, the answer is nuanced. Learning a language does not necessarily increase your innate raw "g" (General Intelligence) or Fluid Intelligence (Gf) in the way that solving IQ test matrices does. You can be a bilingual person with average intelligence.

However, bilingualism does something arguably more valuable than raising your IQ score: It upgrades your brain's Operating System.

Specifically, it upgrades the Executive Control System located in the Prefrontal Cortex—the part of your brain responsible for focus, planning, and ignoring distractions.

In the early 2000s, a Canadian psychologist and Distinguished Research Professor named Ellen Bialystok made a startling discovery that shook the field of psycholinguistics. She found that bilingual children—and bilingual elderly people—were significantly better at tasks that had nothing to do with language. They were better at sorting cards according to changing rules. They were better at ignoring irrelevant visual information. They were better at multitasking in complex environments.

Why would speaking two languages help you sort cards? The answer lies in a cognitive mechanism called Inhibitory Control. And it turns out, the way you learn a language (Translation vs. Immersion) determines whether you build this superpower or not.

This is the comprehensive science of the Bilingual CEO.

Part 1: The War in Your Head (The Conflict Monitoring System)

To understand the bilingual brain, you have to understand that it is never quiet. The bilingual mind is a noisy place.

If you speak English and Spanish, and you look at a picture of a Dog, your brain does not politely decide to only use English because you are currently in New York. Neuroimaging studies using fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and EEG (Electroencephalography) show that both languages are active simultaneously.

- The English neural network screams: "DOG!"

- The Spanish neural network screams: "PERRO!"

This is not a metaphor. Physical neurons representing both concepts are firing at the same time. They are competing for access to your mouth. It is a neurological shouting match, a civil war happening in milliseconds.

If you want to speak Spanish, you cannot just "turn on" Spanish. You have to actively, forcefully, and continuously suppress the English impulse. You have to tell the strongest network in your brain (your native language) to sit down and be quiet.

This suppression requires massive amounts of cognitive energy. It is a top-down command from the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) (the conflict monitor) and the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC)—the CEO of the brain—telling the English centers to inhibit their output. This process is called Inhibitory Control.

The Gym of the Mind

A monolingual person never has to do this. When they see a dog, they just think "Dog." There is no competition. The path from visual stimulus to verbal output is a straight, uncontested highway. A bilingual person performs this act of suppression thousands of times a day. Every sentence, every thought, every word is a rep in the gym of Inhibition.

Over years of practice, this constant mental workout physically changes the structure of the brain. The Prefrontal Cortex becomes denser (Grey Matter increase). The white matter tracts (the cables connecting brain regions) become more robust (Neural Efficiency). This is why Bialystok found that bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on attention tasks. They simply had a stronger muscle for "Ignorning the Distraction," because they have spent their entire lives ignoring their own native language.

Part 2: The Evidence (Stroop & Simon Tasks)

Psychologists do not rely on anecdotes. They use rigorous, standardized tests to measure Executive Control. The two most famous are the Stroop Task and the Simon Task.

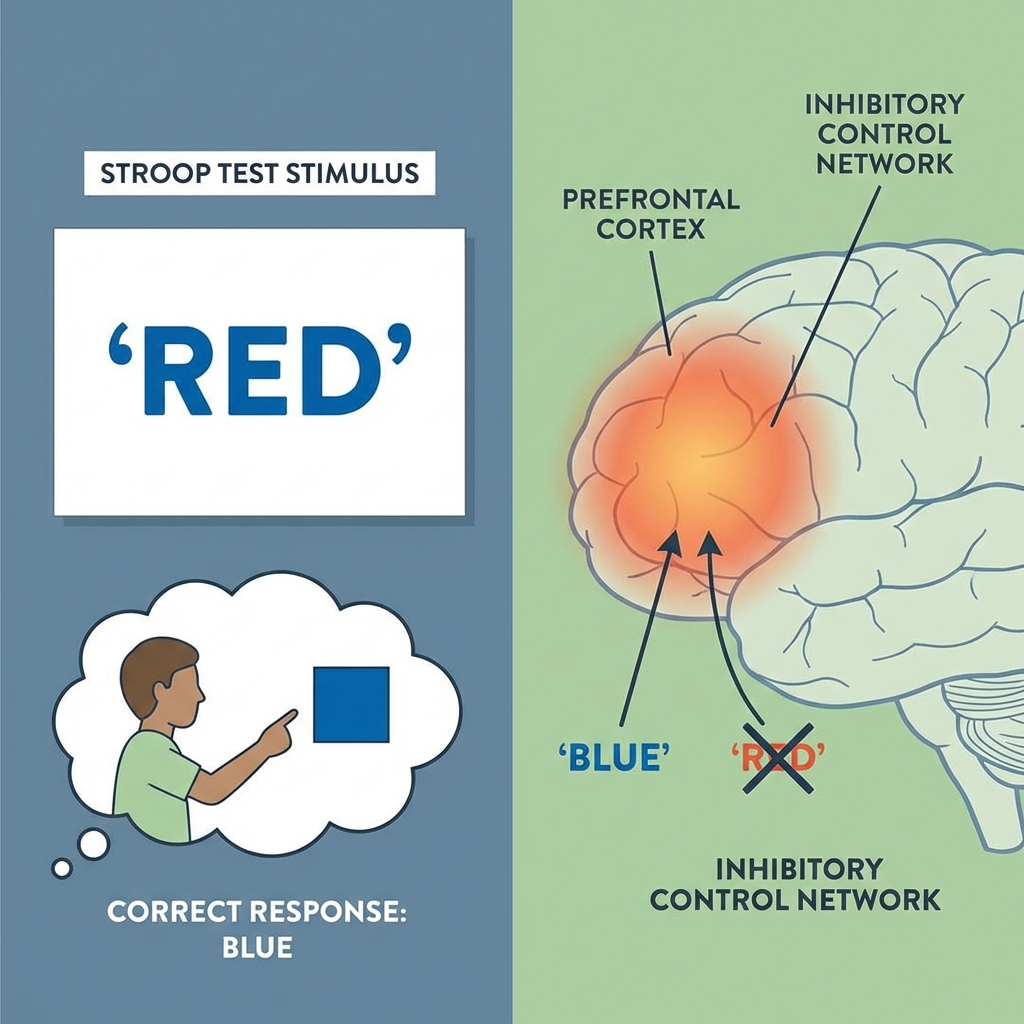

1. The Stroop Task

Imagine you are sitting in a lab. A screen flashes the word: RED But the text is printed in Blue Ink. The tester asks you: "What color is the ink? Answer as fast as possible."

- Your Automatic Brain (System 1) reads the word: "Red!" Reading is automatic for adults; you cannot "not read" a word you see.

- Your Executive Brain (System 2) fights that impulse: "No, wait, stop. The ink is Blue."

This cognitive conflict—the clash between a dominant automatic response and a goal-driven response—mimics exactly what a bilingual brain does every second of a conversation.

- Conflict: My brain wants to say "dog" (Automatic L1), but I need to say "perro" (Goal L2).

The Result: Bilinguals are consistently faster (showing a smaller "Stroop Effect") and more accurate than monolinguals. Their brains are wired to resolve conflict. They can suppress the "Automatic" response (Reading) to focus on the "Goal" response (Color) with less effort and fewer errors.

2. The Simon Task

In this test, a blue square appears on the left side of the screen. You hold a joystick. If you see blue, you must press the button on the right.

- Automatic Impulse: Press left (Spatial compatibility bias). If something is on the left, we want to react on the left.

- Goal: Press right.

Again, bilinguals outperform monolinguals. They are masters of overriding impulses. This ability to decouple the stimulus ("It's on the left") from the reaction ("Press right") is the hallmark of high executive function.

Part 3: Why Translation Cheats the Workout

Now, let's look at how this applies to the Translation Method—the method used by almost every popular language app and high school textbook.

When you learn via the Grammar-Translation method (looking up words in a bilingual dictionary), you are fundamentally altering the cognitive task. You are changing the rules of the game so that you no longer need to inhibit anything.

Immersion Task (The Hard Way):

- Goal: "Understanding the concept."

- Obstacle: "Unknown word."

- Mechanism: Suppress L1. Use context clues in L2. Activate L2 synonyms. Keep the L1 network silent.

- Result: High Inhibition Effort. (Strong Workout). The brain treats L1 as a distraction to be ignored.

Translation Task (The Easy Way):

- Goal: "Find the English equivalent."

- Obstacle: "Unknown word."

- Mechanism: Activate L1 immediately to resolve the tension. "Casa" means "House."

- Result: Zero Inhibition Effort. (No Workout).

When you translate, you are not suppressing your native language. You are inviting it in. You are actively recruiting the English network to solve the problem. You are reinforcing the dominance of your L1. Instead of acting as a CEO who manages two competing employees (English and Spanish) and forces them to work independently, you are acting as a lazy manager who just lets the English employee do all the work while the Spanish employee watches.

This explains the "Paradox of the Fluent Translator." We all know people who have "studied" a language for 10 years, can translate complex texts perfectly, but cannot hold a conversation for 30 seconds. They possess the Declarative Knowledge (Vocabulary + Grammar) but lack the Procedural Control (Inhibition). They learned the content of the language, but they didn't engage the control mechanisms of the language.

Part 4: The Cognitive Cost of Context Switching

Expanded Analysis of "Switching Costs"

One of the most overlooked aspects of translation is the massive "Tax" it levies on your brain's CPU. In computer science, Context Switching is the process of storing the state of a process so that it can be restored and execution resumed from the same point later. It is computationally expensive. If a CPU switches tasks too often, it spends 100% of its time switching and 0% of its time processing. This is called "Thrashing.

Your brain works the same way. It is a biological computer with limited metabolic resources (glucose and oxygen). Every time you switch from L2 ("Reading Spanish") to L1 ("Thinking in English") and back to L2, you pay a Switching Cost.

The Neuroscience of the Switch:

- Disengagement: The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) must send a signal to dampen the active L1 network.

- Reconfiguration: The Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) must retrieve the "Spanish Grammar Rule Set" and bring it into Working Memory.

- Engagement: The Basal Ganglia initiates the new motor plan for articulation.

This cycle takes approximately 300-500 milliseconds. Half a second. If you are translating a 10-word sentence word-for-word, you are context-switching 10 times. That is 3-5 seconds of pure "Administrative Overhead" per sentence.

The "Translation Headache": This is why you get a physical headache after 15 minutes of intensive Duolingo practice. It’s not because the language is hard (the vocabulary might be simple). It’s because you are frantically thrashing between two operating systems. You are overheating the engine. Immersion learners don't get this headache. Once they enter the "L2 State," they stay there. They might feel confusion (Semantic Load), but they don't feel the "Thrashing" (Executive Load). They pay the switching cost once, at the beginning of the session, and then cruise in 5th gear.

Protocol: Minimize switching. Use monolingual dictionaries. Even if a definition is hard to understand, staying in L2 is metabolically cheaper than switching to L1 and back.

Part 5: Code-Switching and the "Bilingual Switch"

Deep Dive into the Caudate Nucleus

You often hear fluent bilinguals mixing languages in mid-sentence. "Voy a la tienda to buy some milk because se me acabó." This is called Code-Switching. For decades, educators viewed this as a sign of laziness or "Semilingualism" (speaking neither language well). They thought the speaker was confused.

The Science says: Brilliance. Recent neurological research shows that Code-Switching is actually a high-level executive function. It is not confusion; it is precision. It calls upon a mechanism known as the "Bilingual Switch."

The "Switch" Mechanism: Researchers Abutalebi and Green (2008) proposed that the Left Caudate Nucleus acts as the physical switchboard operator. When this area is damaged (e.g., in stroke victims with Aphasia), precise code-switching becomes impossible. The patient might involuntarily switch languages (Pathological Mixing) or be unable to switch at all (Fixation).

For a healthy learner, code-switching requires the brain to:

- Map the syntax of Language A to predict where a switch is grammatically legal.

- Identify a conceptual gap (e.g., "Milk" is faster to say than "Leche" in this context) or a social cue.

- Seamlessly toggle the "Language Switch" in the Caudate.

- Inhibit Language A and activate Language B.

- Insert the phrase.

- Switch back.

This happens in milliseconds. It is a virtuoso performance of cognitive flexibility.

For healthy learners, this means that "Control" is just as important as "Vocabulary." You need to train your Caudate. Drill: Practice "Controlled Switching." Tell a story for 1 minute in L2. Then continue the story for 1 minute in L1. Then 1 minute in L2. Do not mix them. Force the switch to be binary and intentional. This strengthens the "On/Off" toggle mechanism, reducing accidental interference.

Part 6: Neuroplasticity: How Language Physically Reshapes You

Expanded Evidence on Structural Changes

We used to think the adult brain was fixed—that once you passed puberty, your neural architecture was set in stone. We now know the brain is plastic throughout life. Language learning is one of the most powerful drivers of Neuroplasticity known to science. It is stronger than learning a musical instrument or solving puzzles.

1. Grey Matter Density: A landmark study by Mechelli et al. (2004) published in Nature scanned the brains of bilinguals and monolinguals. They found that bilinguals have significantly higher grey matter density in the Inferior Parietal Lobule (IPL). This area is associated with vocabulary management and verbal fluency. Crucially, the density correlated with proficiency, not just age of acquisition. The better you learned the language, the denser the brain tissue became. Takeaway: It’s never too late. The harder you study, the denser this region becomes.

2. White Matter Integrity: The brain is composed of Grey Matter (Neurons) and White Matter (Axons/Cables). Using DTI (Diffusion Tensor Imaging), researchers found that the Corpus Callosum (the massive bridge connecting the left and right hemispheres) and the Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus (connecting front and back brain) are thicker and better insulated (myelinated) in bilinguals. This means signals travel faster. It’s like upgrading your brain from Dial-Up to Fiber Optic.

3. Cognitive Reserve (The Alzheimer's Shield): This is perhaps the most profound finding. Because the bilingual brain has spent a lifetime "lifting weights" (Inhibition), it is stronger. It can compensate for damage. When the brain physically deteriorates with age (accumulating Beta-Amyloid plaques and Tau tangles associated with Alzheimer's), the bilingual brain has "backup circuits." It can bypass the damaged areas using the reinforced white matter tracts built by years of Inhibitory Control. Bilingual patients are often diagnosed with Alzheimer's 4-5 years later than monolinguals, even when their brains show the same level of physical decay.

The Prescription: "Use it or Lose it." These structural changes rely on active maintenance. If you stop using the language, the grey matter density recedes within months. You must maintain the "Cognitive Load" to keep the muscle.

Part 7: The Attention Economy & The Filter Bubble

Social Implications of Inhibitory Control

How does this neuroscience apply to your modern life outside of language learning? We live in an Attention Economy. Algorithms (TikTok, Instagram, YouTube Shorts) are specifically designed by PhDs to bypass your Inhibitory Control. They feed you "High Salience" stimuli—bright colors, shock outrage, rapid movement—that trigger your Automatic Brain (System 1).

The Filter Bubble vs The Jargon Bubble:

- Filter Bubble: Algorithms show you what you already agree with (Confirmation Bias). It feels comfortable. It requires zero inhibition of your own beliefs.

- Jargon Bubble: Translating keeps you in what you already understand (L1 Bias). It feels comfortable. It requires zero inhibition of your native tongue.

Both are traps. Both lead to atrophy.

- Breaking the Filter Bubble requires Critical Thinking (Inhibition of bias).

- Breaking the Jargon Bubble requires Immersion (Inhibition of L1).

Language Learning as Attention Training: By practicing strict Immersion (No Translation), you are training the exact neural circuit needed to resist Social Media addiction. You are training the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex to say "NO" to the easy path (Translation/Scrolling) and "YES" to the hard path (Comprehension/Focus).

The "Deep Work" Connection: Cal Newport defines Deep Work as "Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit." Speaking a second language is Deep Work by default. You cannot multitask while speaking Spanish. If you check your phone while speaking L2, the sentence collapses. It demands 100% of your RAM. Use language learning not just to acquire words, but to re-train your ability to focus in a fragmented world.

Part 8: The Mental Gym Protocols (Consolidated)

How do you turn language learning into a deliberate cognitive workout? Here are three protocols used by polyglots and cognitive scientists.

1. The "Switching" Drill (Caudate Training)

- Goal: Strengthen the mental toggle.

- Action: Read a paragraph in L2 for 2 minutes.

- Switch: Immediately switch to a high-demand task in L1 (e.g., write a shopping list or solve a math problem) for 2 minutes.

- Switch Back: Immediately go back to L2 reading.

- Why: This forces the global network to reconfigure rapidly. It prevents "Language Mode" inertia and forces the ACC to exert top-down control.

2. The "Stroop" Reading (Inhibition Training)

- Goal: Train suppression of the automatic response.

- Action: Read a text in L2.

- Rule: Every time you see a specific common function word (e.g., "the" in English, "el/la" in Spanish, "le/la" in French), do NOT read it aloud. Instead, clap your hands or tap the table.

- Why: This forces you to inhibit the "Reading Impulse" continuously. You must monitor your own output and intercept the "Automatic" reading process before it reaches your lips.

3. The "Pure L2" Hour (Deep Work)

- Goal: Maximize metabolic load on the Prefrontal Cortex.

- Action: Set a timer for 1 hour.

- Rule: The "Monastic Rule." No English inputs. No English outputs. No English thoughts (if possible).

- Constraint: If you don't know a word, you must circumlocute (describe it) or draw it. You may not look it up.

- Why: This simulates the "Immersion Environment." It forces the brain to construct meaning from limited resources, maximizing the "Generation Effect" and keeping the Inhibitory Control system active for a sustained period without relief.

Part 9: The "Foreign Language Effect" on Morality

Did you know you are more logical in a second language? Studies show that massive changes in decision-making occur when we switch languages. When presented with the famous Trolley Problem (Kill 1 person to save 5), people are significantly more utilitarian (more likely to push the man) when the dilemma is presented in their L2 compared to their L1.

Why? Emotional Distance. In L1, the words "Kill" and "Push" trigger deep emotional resonance in the Amygdala. The emotional brain screams, "Don't push the man! It's murder!" In L2, the words are "Tags" or "Labels." The emotional resonance is dampened by the cognitive load. The Amygdala is quieter, and the Prefrontal Cortex (Logic) takes over. It says, "5 is greater than 1. Push him."

This Foreign Language Effect allows you to make cooler, more rational decisions. Business leaders often negotiate better in L2 because they are less triggered by emotional language or insults. They can appraise the deal purely on the numbers. By learning via text clarification and immersion, you are training yourself to be a Rational Actor.

Part 10: Conclusion: The CEO Mindset

Don't delegate your thinking to your native language. When you feel the urge to translate, recognize it for what it is: A desire to give up control. A desire to let the automatic L1 take over. A desire to be a lazy employee in your own mind.

Resist it. Stay in the uncertainty. Use the L2 explanation. Force your brain to resolve the conflict internally. It will feel harder. It will feel slower. It will feel frustrating. But you aren't just memorizing vocabulary. You are building a better brain. you are insulating your neurons against aging, you are training your focus against algorithms, and you are taking control of your cognitive destiny.

You are becoming the CEO of your own mind.

References:

- Bialystok, E., & Martin, M. M. (2004). Attention and inhibition in bilingual children: Evidence from the dimensional change card sort task. Developmental Science, 7(3), 325-339.

- Abutalebi, J., & Green, D. W. (2007). Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language control. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 20(3), 242-275.

- Mechelli, A., Crinion, J. T., Noppeney, U., O'Doherty, J., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S., & Price, C. J. (2004). Structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature, 431(7010), 757-760.

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Grand Central Publishing.

- Costa, A., et al. (2014). Your Morals Depend on Language. PLOS ONE.